According to the Hebrew Bible’s patriarchal narratives, Israel was 50% Aramean and in turn his offspring was no less than 75% Aramean on average (with the possible exception of four of his sons born to handmaidens).

Regardless of those narratives’ historicity, which is not the topic of discussion here, such an accumulation of Aramean admixture would make Israel’s tribal ancestors a genetically Aramean nation via the repeated taking of Aramean wives (both Bethuel and Laban are labeled “Aramean”) and should give one pause, to say nothing of the famous passage referring to Israel as a “wandering Aramean” (Deut. 26:5).

It does say something about the Ancient Israelites’ self-perception, how they understood their own kinship in relation to neighbouring peoples and sheds a rare light on the nature of those relations which weren’t necessarily negative or hostile (a cliché if there ever was one). It also testifies to the prominence the Arameans held in their cultural universe and collective unconscious.

As of late, the Arameans have become a topic of discussion beyond the realm of dry academic debates and the Assyrian-Aramean naming controversy, primarily in the context of heated exchanges surrounding the contemporary identity issues of Levantine Arabs. It isn’t exactly rare to see people claim the Phoenicians spoke Syriac for instance, and Aramaic as the “the language of Jesus” or “the ancestor of Arabic & Hebrew” are among the platitudes one can easily encounter online nowadays.

So who were the Arameans, and what do we owe them exactly?

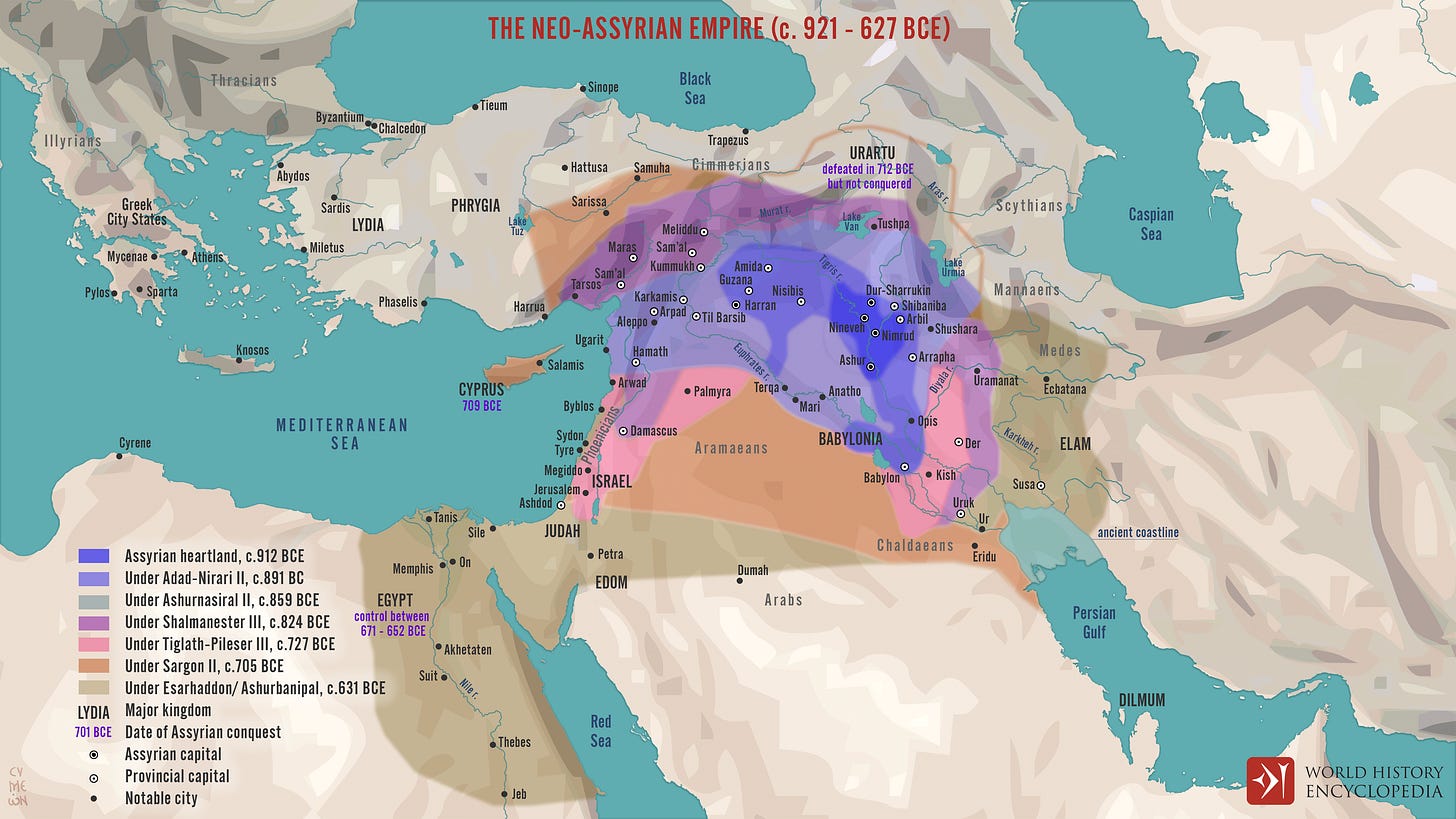

The earliest attestation of the Arameans goes back to the Aḫlamû (a term derived from the ǵ-l-m root and possibly meaning “youths”, cognate with the Hbr. ˁelem & Arb. ġulām) mentioned in Middle Assyrian texts (11th century BCE) where they are described as semi-nomadic agropastoral groups who occupied much of the area between the Euphrates and Orontes valleys in what is now Northern & Eastern Syria. “Aram” seems to have only rarely seen use as an endonym, it was a geographical label for the most part (as seen in the Sefire treaties, c. 8th century BCE).

In truth, their origins are very much shrouded in mystery, and will remain so for the foreseeable future. By the beginning of the 1st millennium BCE, the Arameans constitued themselves in separate polities in much of the area where the Aḫlamû are assumed to have been active.

From an archeological standpoint, these polities find their source in small settlements that appeared rather suddenly at the end of the Late Bronze Age and increased drastically in number during the Iron I (~1200-1000 BCE) and were characterised by a distinct material culture which featured a shared rural economy alongside an “egalitarian” structure and architecture. If any of this sounds oddly familiar, it is because the exact same process is seen in the highlands of Judea-Samaria during the same tumultuous period and leads to the emergence of the Proto-Israelites and later Hebrew kingdoms.

In both cases, reshuffling of the earlier LBA population seems to be involved in the formation of the new ethnic polities, in this particular case we’re mostly dealing with what was left of the Amorites in the area (while Canaanites are the main agent behind this in-situ reshuffling process in EIA Israel). Because of the strongly multi-ethnic character of Syria’s demography during the LBA, it is no coincidence if the emergence of the Aramean kingdoms went hand in hand with that of the Neo-Hittite states.

The picture obtained from the linguistic evidence for Aramaic’s early stages is much more ambiguous. What really is at stake here isn’t so much the Central Syrian koiné from which Old Aramaic would later emerge as the international language of its age, but rather the classification of the more obscure languages that are at first glance very similar to Aramaic but appear to preserve archaic features that seemingly bring them closer to either Canaanite or Ugaritic.

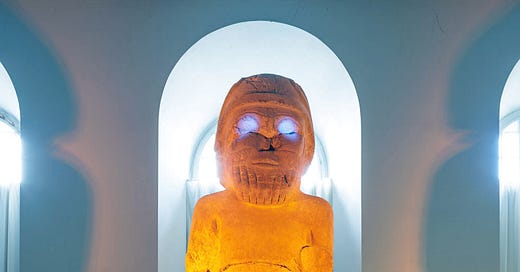

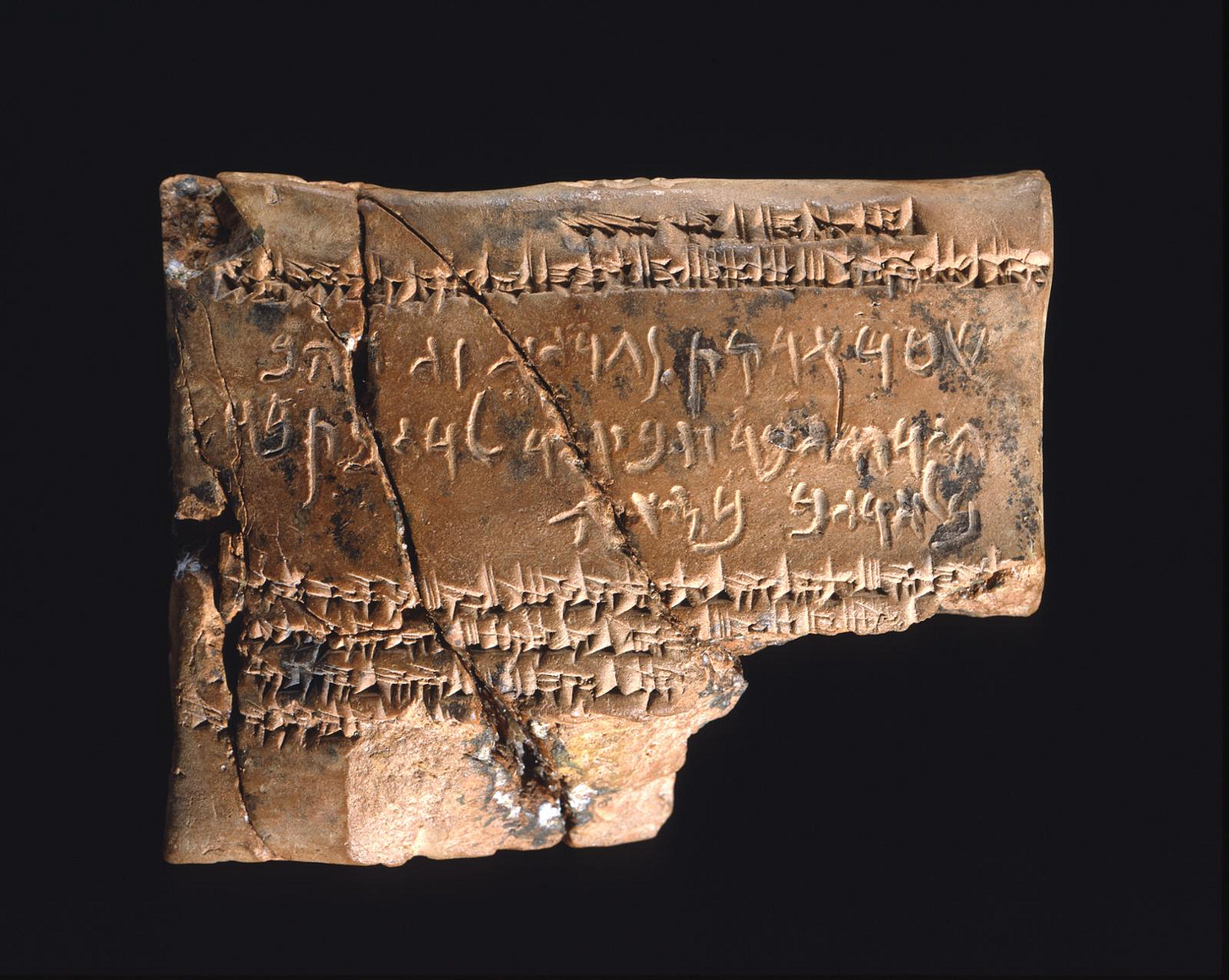

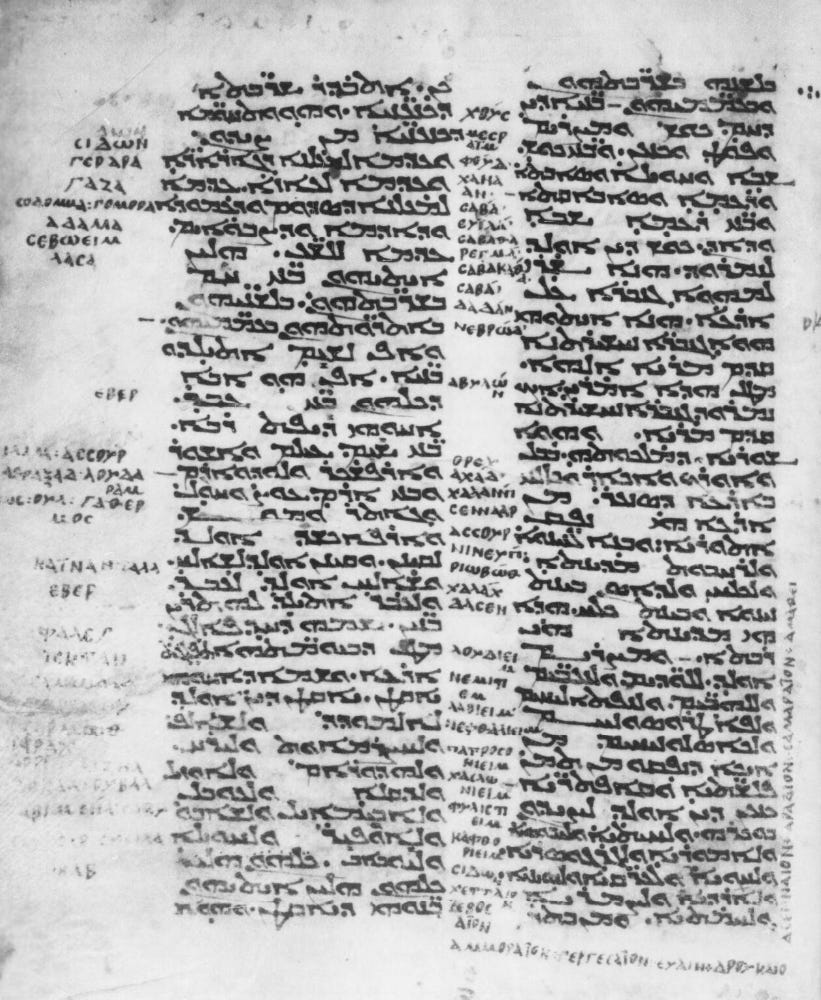

Sam’alian (AKA “Ya’udic”), the language of the mid-8th century statue at the beginning of this post which bears Panamuwa I’s dedicatory inscription to the storm god Hadad, is arguably one of the best examples. This language continues to frustrate most attempts at classification, in no small measure because of its internal diversity which exhibits varying degrees of similarity to the Central Syrian dialects of Old Aramaic and the earlier use of Phoenician (Tyrian) as the prestige language in 9th century inscriptions (and this apparently spilled over into the local language).

Sam’alian is sometimes seen as a mixed Canaanite-Aramaic dialect (whereby a local Phoenician-speaking population was ruled by an Aramaic-speaking elite), a divergent dialect of Old Aramaic or a distinct Northwest Semitic language (the latter being Huehnergard & Pat-El’s view). The latter view relies largely on the retention of the nominative and oblique case distinction in masculine plurals, as well as the presence of a (reconstructed) N-stem form.

Factually speaking, neither really warrant classifying Sam’alian as a distinct NWS language on its own, first because it was spoken on the periphery of the Semitic world (the -uwa ending for instance is a hallmark of Luwian i.e. Anatolian personal names) and so archaic traits are to be expected and secondly because while it is true that Aramaic is characterised by a rigid verbal structure consisting of six stems (three active and three passive/reflexive) the use of such stems is seldom useful in classifying languages at such a granular level and in this case we are really dealing with an argument from silence based on a reconstructed form (which, if correct, can still be understood as an archaic trait). Regardless of those subtleties I for one would argue that the Sam’alians’ devotion to the storm god Hadad, whose worship constitutes a shared religious and cultural trait throughout the Aramean world of the first half of the 1st millennium BCE, further strengthens the case in favour of a closer relationship to Old Aramaic.

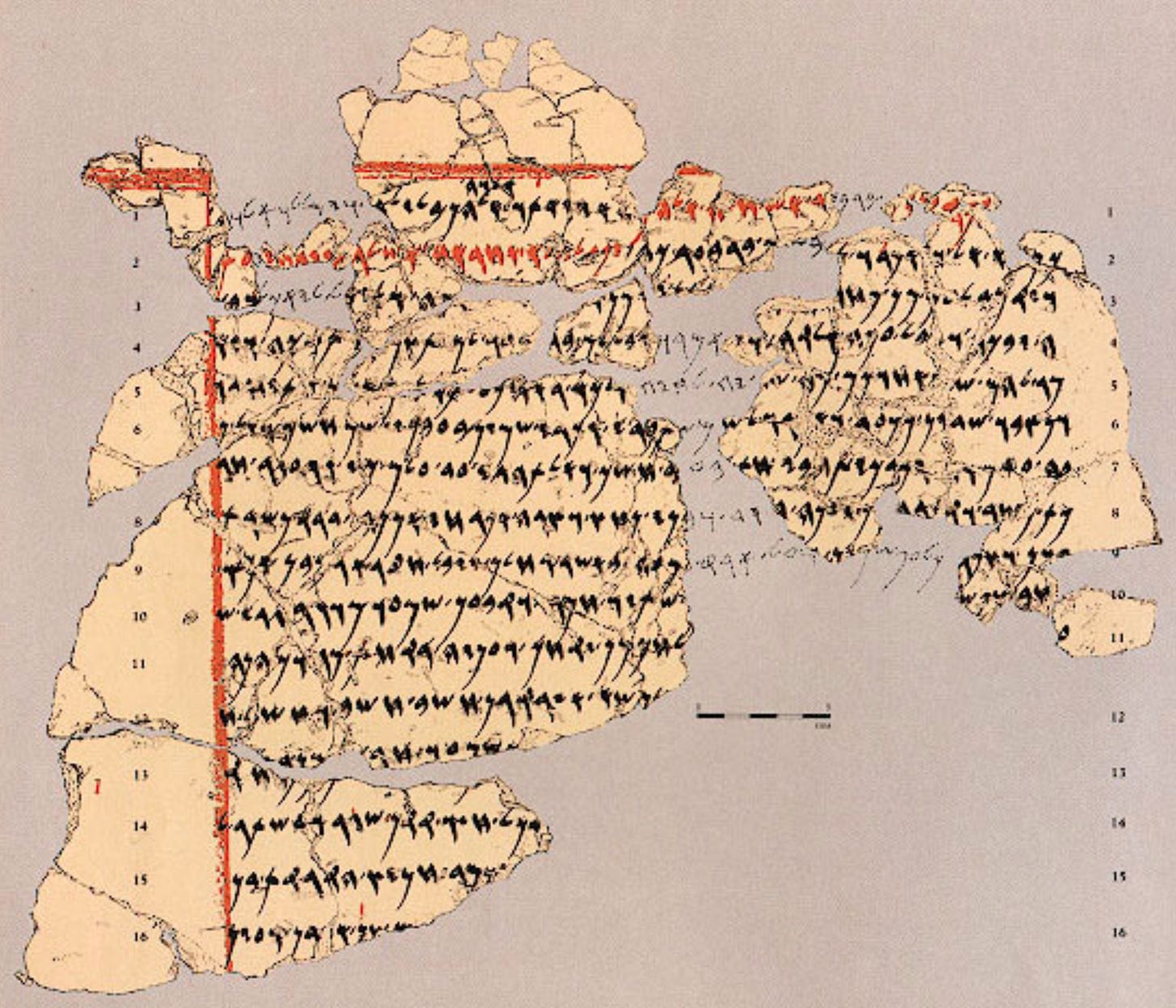

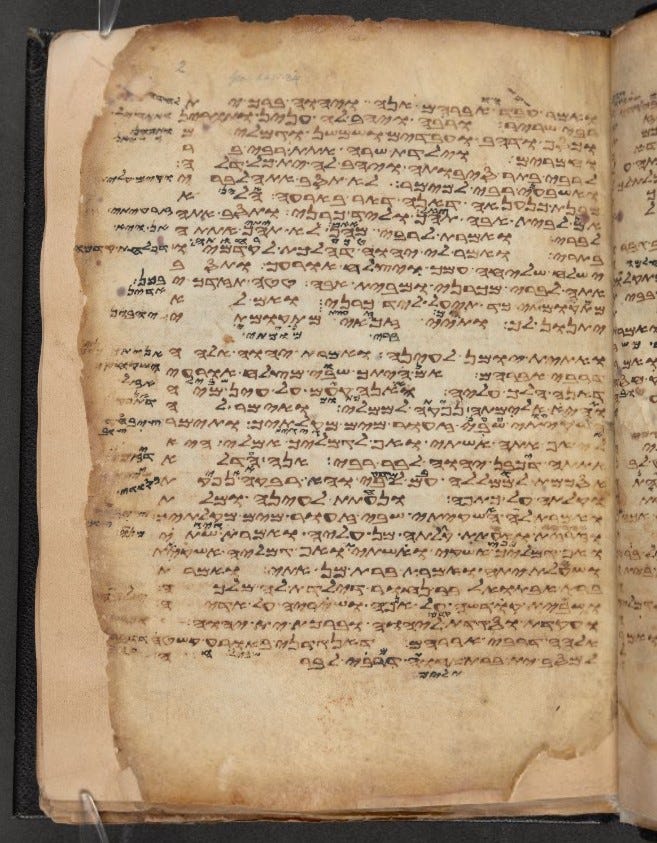

An even more convoluted debate surrounds the classification of the Deir Alla plaster texts, to make a long story short my understanding is that we might be dealing with a divergent Ammonite dialect that was closer to Aramaic within the NWS dialect continuum. But until more texts in this language come to light, this will inevitably remain a controversial stance. It should be remembered that in the narrative arc from the book of Numbers, the seer Balaam b. Beor (the main character of this inscription which therefore constitutes one of the most ancient extra-Biblical attestations of a character from the Pentateuch) is described as coming from “Petor” in Aram-Naharaim (Num. 22:5) which is usually identified with the town of Pitru (known from Middle Assyrian texts, situated quite close to Sam’al & visible on the map of Aramean polities above).

While Pat-El & Wilson-Wright’s Aramaeo-Canaanite subgroup is quite convincing (the common innovations uniting Aramaic and Canaanite are sound), to which I would adduce several other innovations especially in the realm of shared irregularities, the situation might actually be closer to the “Aramoid” subgroup put forth by Kogan (2015). It must be kept in mind that the early 1st millennium NWS speech area was for all intents and purposes a dialect continuum and that many of the traits seen as common innovations could have spread areally much like the definite article did (indeed, within Canaanite, several isoglosses bring Hebrew-Moabite-Ammonite closer to Aramaic for example).

Another theory worthy of mention might be Peter Stein’s hypothesis positing a closer relationship between Aramaic and Sabaic, also on the basis of interesting similarities in both languages’ derived stem system (and glaring dissimilarities when compared to other Old South Arabian languages), an interesting theory considering Sayhadic’s problematic internal classification issues, it might well be that Sabaic represents a linguistic type closer to NW Semitic which arrived in SW Arabia by the end of the second millennium BCE (possibly bringing the Musnad along with it) though such a theory needs more than mere parallels in the derived stem system to work.

Pinpointing the origin of the Arameans to a specific area, if there ever was a single departure point, seems to be a rather pointless endeavour. A well-known passage in Amos 9:7 famously downplays the Israelite Exodus from Egypt by comparing it to Yahweh having brought Philistines from Caphtor (Crete) and, more importantly, the Arameans from the "land of Qir”.

This area seems to have been in the Euphrates valley, possibly close to the city of Hīt in present-day Iraq, which is in-keeping with the description of the Aḫlamû of Middle Assyrian texts.

The ancient genomic evidence might on the other hand suggest an origin closer to the Levant, as many of the LBA-EIA samples for which an association with early Arameans is likely point towards the western part of the Fertile Crescent.

Beyond the singleton from Abel-beth-Maacah (I2201) which is known to have been part of a chain of Aramean kingdoms in the Hula valley and Golan (Geshur is another example of one such kingdom, Bethsaida most definitely is an Aramean site), several samples from Lebanon, SE Turkey and Northern Iraq are also bound to be of Aramean descent.

The Middle Assyrian sample from LBA Nemrik 9 (I6441) carried J-FGC15940/Y6094, a sub-branch of YSC76 that also made an appearance in Iron III Beirut, this branch has long been a prime contender for an association with the Arameans and is found in present-day Assyrians. YSC76 comprises other sub-branches that are likely to have Aramean associations as well, it seems to have been quite successful in the Syrian desert and so that makes it a prime contender regardless of the finer details.

Another similar branch would be E-FGC18401, which was found in Iron Age Anatolia (NEV030 from Nevalı Çori). This sample also finds itself at the right place and at the right time for such an association to work, the branch’s distribution and phylogeny resembles what is seen with FGC15940.

Yet another Y-line which can convincingly be tied to the Arameans would be T-FGC80981 and its Y7794 subclade in particular which proves to be a very close fit in time and space tracking Aramean dispersals despite lacking the ancient data to verify the correlation (I2201 from Abel-beth-Maacah also clusters underneath T-CTS2860, which slightly increases the odds that the correlation is correct).

One should also remember that because of the multi-ethnic context in which the Arameans emerged, much of their territory having been the heartland of the Mitanni kingdom and later part of the Hittite empire immediately prior to their emergence during the LBA, some Y-lines that were not originally tied to NWS groups (let alone Semitic-speaking ones) might have re-expanded with them as well, this could hold true for branches like R-L945 if we assume a broadly Anatolian (Luwian?) background for this line beforehand, but this is much harder to prove at this stage. This inherent complexity extends to the leftovers of other ethnic groups (Hurrians, Indo-Aryans, etc) that once coexisted with the Amorites in LBA Syria.

What made Aramaic great was not the military prowess of the Aramean polities in Central Syria that nurtured it into a chancellery language, but rather the lingering shadow cast over it by the Neo-Assyrian (and later Babylonian and Persian) empire.

The Arameans formed a coalition that saw the kingdoms of Israel, Aram-Damascus, Hamath, Ammon, the Qedarite Arabs (under the leadership of Gindibu, technically the first mention of the Arabs in the historical record) and the smaller Phoenician and Syro-Hittite states join forces and put an effective halt to Assyrian expansionism at the battle of Qarqar circa 853 BCE. Instead of using the momentum to enshrine their gains, the Levantine coalition quickly dissolved and returned to its usual quarrels.

Infighting ensued with the kingdom of Aram-Damascus establishing its own empire and eventually occupying much of Israel (and destroying Eqron in the process around 830 BCE) under Hazael’s reign (to whom the Tel Dan stele, which famously mentions the “House of David” and boasts of having defeated both of the Hebrew kingdoms and killing their respective kings, is usually attributed).

The Assyrians would return a century later and effectively assert control over the entire region from the mid-8th century onwards. The unintended consequence of their steady conquest of the Aramean kingdoms, coupled with earlier waves of Aramean migration to Mesopotamia proper and their imperial policy of forced resettlement, was the increased use of Aramaic not only as a spoken language but as an administrative one as well.

In many ways, the Assyrian empire provides striking parallels to the Roman empire. From its humble beginnings in Northern Mesopotamia as an Amorite kingdom to the presence of an earlier native people which profoundly impacted its civilisation (the Sumerians provide an interesting if warped parallel to the Etruscans) and the inability of its enemies to thwart its expansion despite scoring victories (much like how Pyrrhus’ eponymous victories in southern Italy were more of a nuisance to Rome’s enemies and nothing more than a temporary setback to Rome’s growth). In the grand scheme of things, the Aramaisation of the Neo-Assyrian empire can be compared to how Greek culture slowly crept into and irreversibly infected the Romans’ old Latin culture after the takeover of Magna Græcia. To paraphrase Horace, conquered Aram took captive its Assyrian conqueror and wove its language into the very fabric of Mesopotamian imperialism.

The adoption of the Central Syrian Aramaic koiné and its meteoric ascent was also a conscious choice of Assyrian linguistic policy. Its close linguistic proximity to the Canaanite dialects by virtue of its being part of a broader Northwest Semitic continuum and the similarity of its consonantal script to the other variants of the Phoenician script in use in the Levantine kingdoms made it a weapon of choice so to speak. Another parallel to the Roman empire might be how the disappearance of the Canaanite dialects owes much to Aramaic’s similarity to those dialects, every bit as much as Gaulish, Celtiberian, Ligurian, Lusitanian and Brittonic’s decline owed much to their similarity to Latin. The main difference is that the Romans were imposing their own language in Gaul, Hispania and Britain, while Aramaic is a very peculiar case of a language riding the wave of foreign conquest.

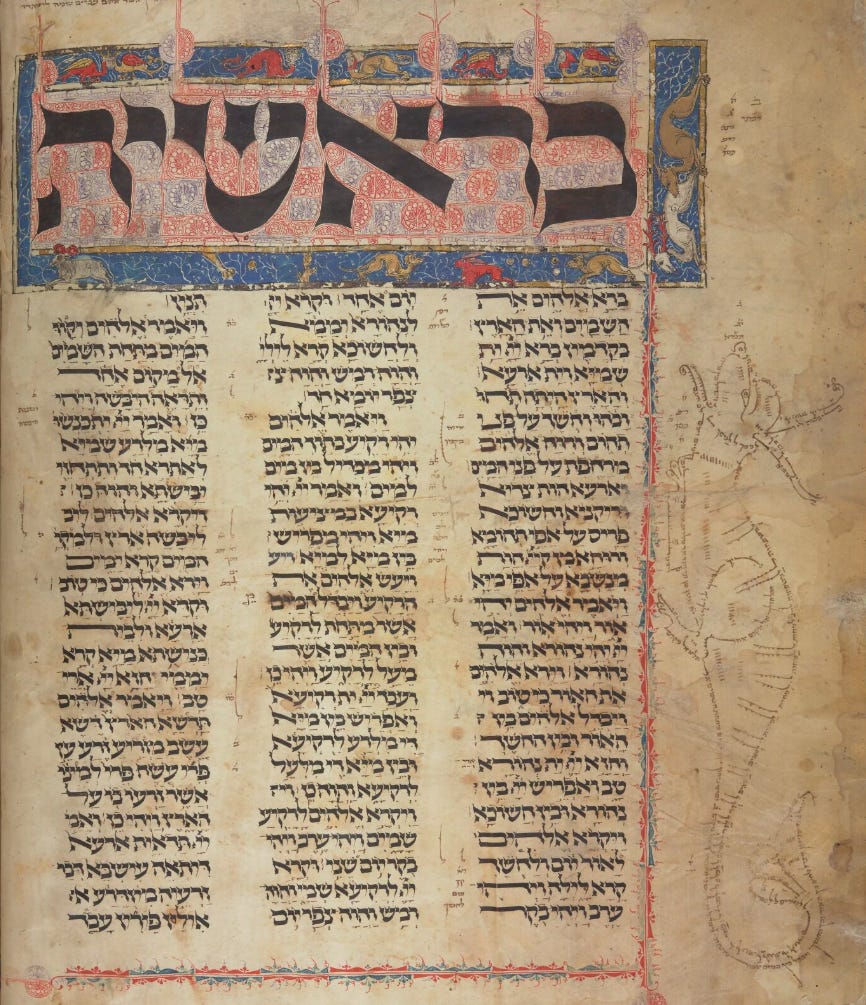

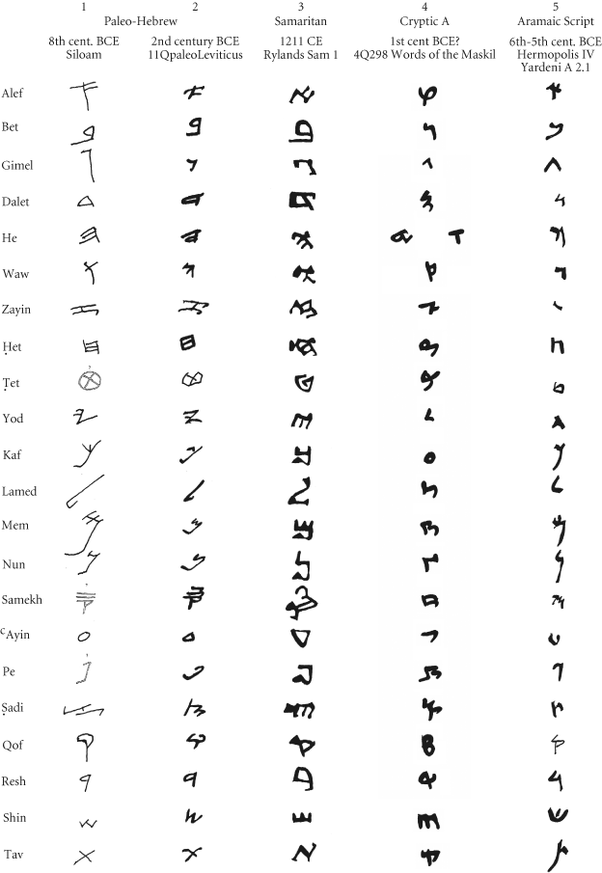

Speaking of the Phoenician script, matres lectionis or the use of consonantal signs for long vowels (Heh 𐤄 for /ā/ & /ē/, Waw 𐤅 for /ū/, Yodh 𐤉 for /ī/) are an Aramean innovation, the spelling of Phoenician is otherwise almost completely defective (vowels are rarely if ever indicated) and remained that way throughout the first half of the 1st millennium BCE, whereas matres lectionis are present in the earliest Old Aramaic inscriptions. The use of matres lectionis spread to Hebrew and Moabite (where Heh 𐤄 is used for the 3rd masc. sg. possessive clitic -ō), though only partially and the Masoretic Text of the Hebrew Bible conserves a lot of the defective consonantal spelling typical of early inscriptions (this is much less true of the Samaritan Pentateuch, which makes more extensive use of matres lectionis, so despite using the Paleo-Hebrew script the spelling is less archaic).

It is possible that this Aramaic innovation is what eventually led to the appearance of vowel signs in the Archaic Greek alphabets (also derivates of the Phoenician script), as there are a number of correspondences between the letters used to signify long vowels in the Old Aramaic script and vowel signs in the Western and Eastern Greek alphabets (including the Euboean variant which would give rise to the Italic alphabets).

Little wonder then that by the time the Assyrians besieged Jerusalem in 701 BCE, the Judahite elite was already fluent in Aramaic (see 2 Kings 18:26). This policy of Aramaisation would continue unimpeded under the Babylonian empire, and was enshrined by the Achaemenid empire.

The practical brand of imperialism embraced by the Persians saw the creation of a new literary standard for the language, Imperial Aramaic. This was accompanied by the institutionalisation of the cursive script used by Aramaic-speaking scribes.

It is under Achaemenid rule that the native cuneiform tradition of Mesopotamian scribal culture would be utterly eclipsed by the Aramaic one. From Egypt to Afghanistan, Imperial Aramaic was the language of trade, taxes, imperial edicts, proclamations and private correspondence, it is during this period that Aramaic became a truly international language. The language would outlive this empire as well and take on a life of its own outside the realm of chancellery and administration.

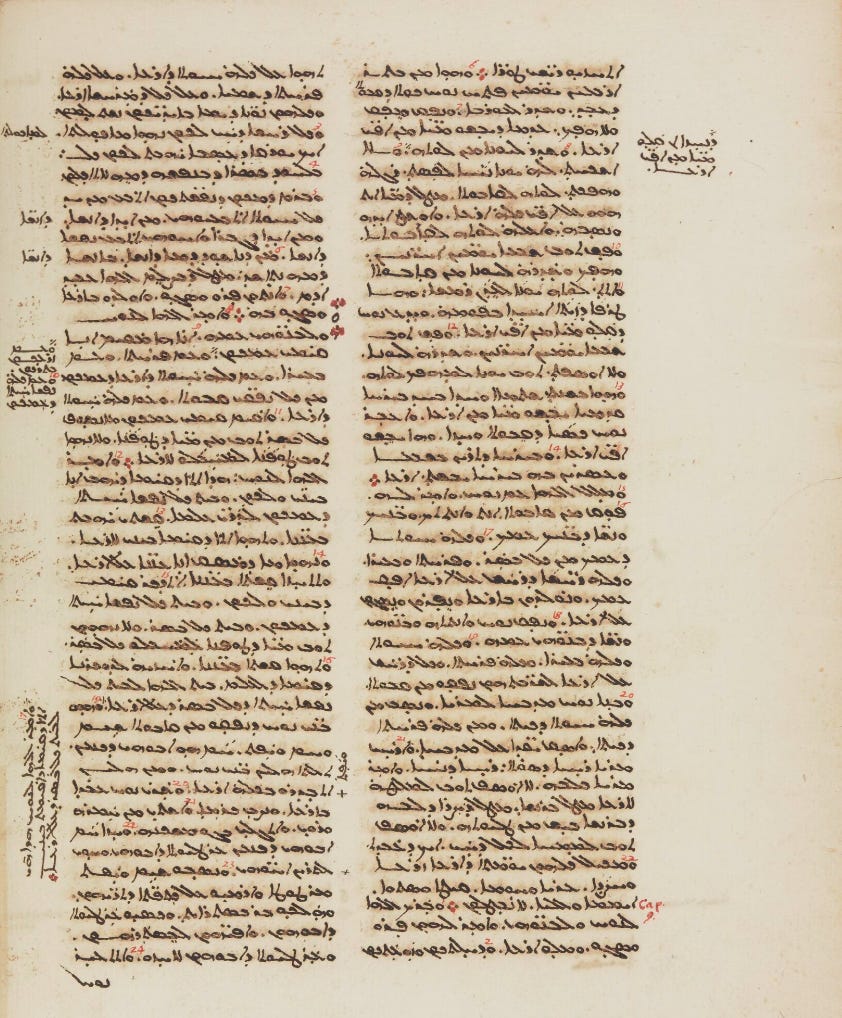

The official Aramaic language of the Achaemenid empire has come down to us in the form of numerous documents, Egypt being where most of those documents (such as the Elephantine Papyri) were found thanks to the dry climatic conditions which enabled their preservation, it is also the language in which the books of Daniel and Ezra were written (the language is often labeled “Biblical Aramaic”, though it really is Imperial Aramaic).

The Imperial Aramaic script, a cursive version of the Phoenician script where the upper part of the letters is shorn off, would fare just as well and its derivates would be used not only to write down the local languages spoken in the Fertile Crescent (from Hebrew to Arabic alongside a slew of local Aramaic languages) but Middle Persian and the language of the Parthians (Pahlavi script) as well as the languages of the Indian subcontinent (Brahmic scripts). Arabic, Hindi, Persian, Tamil, Hebrew, Tibetan and many other languages all use writing systems that sprang from the Aramaic script.

By the turn of the millennium, Aramaic already was a language family subdivided into two clearly distinguishable branches, an Eastern (or Mesopotamian) one and a Western (or Levantine) one. This stage is better known as “Middle Aramaic”. After the fall of the Achaemenid empire, Aramaic was no longer regulated by any single imperial authority and began to diversify without any constraints.

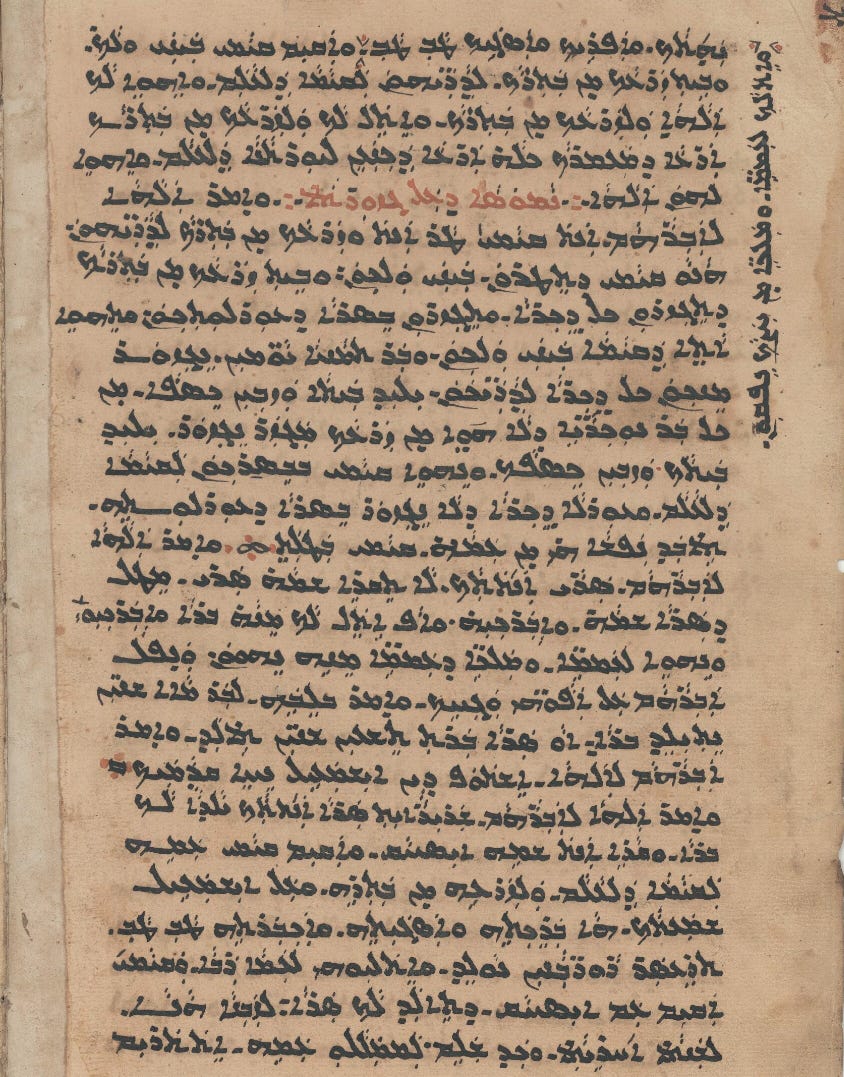

This is when languages such as Palmyrene, Hatran and Nabatean Aramaic arose. One of these, an Edessan dialect better known as Syriac (and a close relative of Palmyrene and Hatran), became a classical language that would produce a rich literary, poetic, scholarly and liturgical tradition of its own that forms the basis of the Eastern Churches’ rite.

Because of the Christian context in which Syriac thrived, Greek also had a substantial impact on the language’s lexicon. For this reason, it is mainly through Syriac that much of Classical Antiquity’s surviving literature was translated and transmitted to an Arabic-speaking audience.

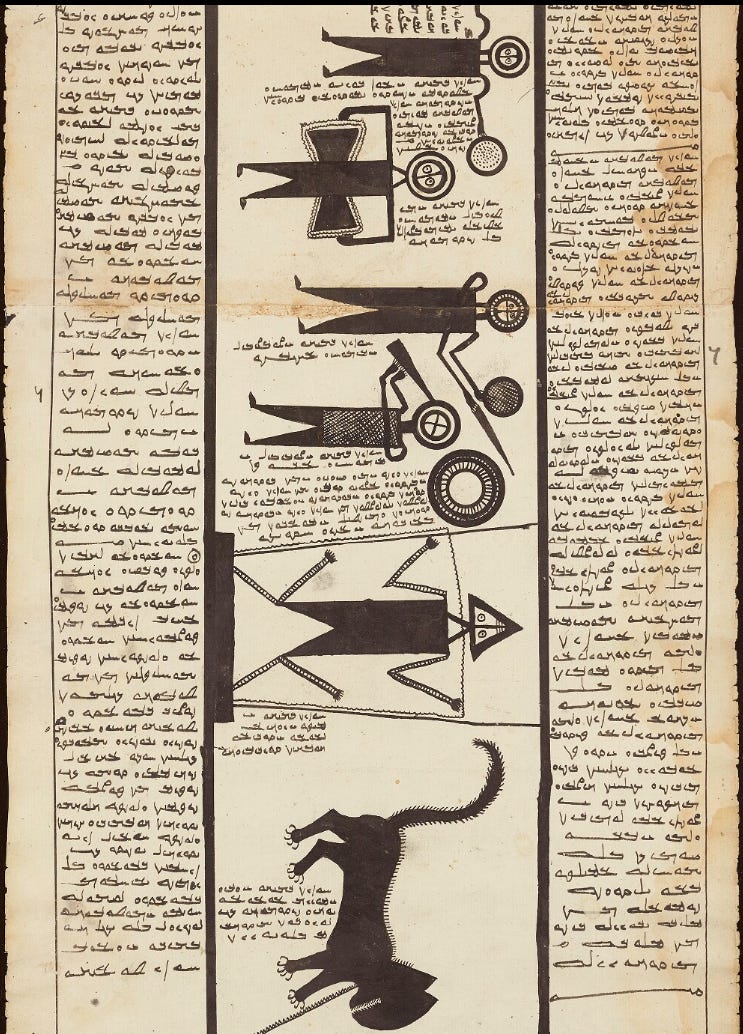

The Eastern branch to which Syriac belongs is heavily coloured by earlier layers of Assyrian and Babylonian speech (both dialects of Akkadian) alongside a Persian superstrate. This holds true of the two other Eastern Aramaic languages which produced a rich literary tradition of their own, namely Jewish Babylonian Aramaic, the language of the Babylonian Talmud, and Mandaic which is the language of the last surviving gnostic religion (both are derived from Late Babylonian Aramaic, it is also likely that the Mandæans are at least in part of Judean descent).

The Western branch in comparison tends to have an important Canaanite substrate (not true of all varieties however, think of Nabataean Aramaic), and for the literary languages that arose from it either a Hebrew or Greek superstrate. Unsurprisingly it is mainly Jewish Palestinian Aramaic (JPA; the language of the Jerusalem Talmud) and Samaritan Aramaic that have a Hebrew superstrate while Christian Palestinian Aramaic (CPA; a descendant of Judean Aramaic) has a very pervasive Greek component.

This brings us to Jesus’ language. As should be clear by now, there no longer was a unitary Aramaic language in the 1st century CE, but rather a set of dialects or languages belonging to two fairly distinct branches with varying degrees of mutual intelligibility. Jesus’ everyday language would have been Galilean Aramaic, a dialect that developed into JPA (despite its name, the Jerusalem Talmud was not written in Jerusalem but in the Galilee, which was the main area of Jewish settlement after the Bar Kokhba revolt).

The centuries which preceded the birth of Jesus saw a constant decline in the use of Hebrew, a phenomenon that was slowed down by the re-emergence of Hebrew nationalism in the wake of the Maccabean revolt and the re-establishment of Jewish sovereignty with the rise of the Hasmonean kingdom. Hebrew was by no means a dead language, Mishnaic Hebrew (Rabbinic Hebrew) is now known to have been a spoken variety of Late Biblical Hebrew - albeit heavily influenced by Aramaic - and would remain that way until the 4th century. Jesus should then have been familiar with Hebrew alongside his own native Galilean Aramaic, even if Hebrew is likelier to have survived as a spoken language in the Judean desert and in Peræa than in the Galilee (Rendsburg’s theories about Mishnaic Hebrew being a Galilean dialect notwithstanding). Hebrew would also be boosted for nationalistic purposes during the Bar Kokhba revolt, roughly a century after Jesus’ death.

Such was the prominence of the Western Aramaic dialects in 1st century Judea that when Flavius Josephus speaks of “our tongue” he refers not to Hebrew but to Judean Aramaic (his first draft of The Jewish War was also in that language), clearly demonstrating that Aramaic’s Judean-Samaritan-Galilean dialect(s) had become the majority language(s).

To claim that “Jesus spoke Aramaic”, while correct in a broad sense, muddies the waters to a great extent. To assume that a present-day speaker of Turyoyo or even Ma’louli Aramaic (one of the few surviving Western Neo-Aramaic dialects) speaks “the language of Jesus” would be tantamount to imagining that Tamerlane and Beyazid I could converse in the same Turkic language.

More importantly, because of Late Biblical Hebrew’s survival and its prestigious status as the ancient language of the nation, it is no surprise if many of his sermons make sense only if they were delivered in Hebrew (which gives meaning to the double-entendre and quips used in those sermons, a feature not only of Biblical discourse but of Rabbinical [especially Haggadic] literature as well, many of those nuances are simply lost in Aramaic).

Aramaic’s eastern and western dialects would continue to be spoken for many centuries, in the Levant it remained the majority language well into the 10th century CE and survived later still in Lebanon and Syria’s mountaineous terrain (as in Ma’loula, where an unwritten variant of Western Aramaic remains the spoken language). In Mesopotamia the language fared even better, to this day Sureth (which is not a descendant of Syriac despite its name, although it might be descended from a very close relative) alongside a slew of Neo-Aramaic dialects remains spoken by hundreds of thousands if not over a million speakers (essentially Assyro-Chaldeans) despite considerable loss in diversity and repeated attempts at forced Arabisation, Kurdification and Turkification of its speakers over the years (the Jewish dialects have practically vanished for similar reasons).

Here too, this is hardly surprising considering that the early Arabian Muslims were in the habit of calling Mesopotamia’s rural population “Nabateans” because of the shared use of Aramaic vernaculars.

Similarly to how Aramaic’s close similarity to its NW Semitic sister languages hastened the latter’s demise, Arabic’s resemblance to its far-flung Central Semitic cousin doomed Aramaic to a slow and agonising death.

Much is made of the Aramaic substratum in spoken Levantine Arabic, and indeed the claims that Levantine Arabic isn’t Arabic but rather Aramaic or even Canaanite in an Arabic guise (“Neo-Canaanite” according to a famous dilettante from Amioun) are particularly grotesque, nevertheless anyone with even a passing knowledge of Classical Syriac or Targumic Aramaic would be able to notice the old tongue’s lingering influence.

To cite only a few examples:

The 3ps. masc. pl. personal pronoun henne (Syriac hennen)

The 2nd and 3rd ps. masc. pl. clitics -kon, -(h)on (compare Syriac -ḵon & -hon)

The confusion between ˀilā “towards” and ˁalā “upon, on” (also a feature of Israelite Hebrew in the Book of Kings).

Prepositions such as ǧuwwa “inside” (Syr. gawwā) and barra “outside” (Syr. barrā).

The use of l(a)- as a directive, accusative and genitive marker.

Loss of endings in possessive pronouns, qualitative vowel moved backwards (laka > lak/laˀelak).

The shift of /ṯ/ > /t/, /ḏ/ > /d/ and even /ṣ/ > /z/ (ṣaġīr > zġīr), the deletion of vowels in opening syllables (such as the /a/ of ṣaġīr) corresponding to an Aramaic schwa.

Some of these, especially in the realm of sound changes, should be viewed with caution as the plosive-spirantised realisation of stops (more on that below) so typical of post-Official Aramaic dialects is nowhere to be found in spoken Arabic.

Where Aramaic’s influence on spoken Levantine Arabic is most keenly felt however is within the verbal system. The system of complex inflections inherited from Classical Arabic underwent a complete overhaul and was replaced with a system that closely follows what is seen in Aramaic, consider for instance the opposition between katabet “I wrote” and katbat “she wrote” (compare Syr. keṯbeṯ & keṯbaṯ) or the loss of the dual as a productive category.

The increased use of the active participle as a regular present (as in ˀanā ˁāref “I know”) is another plausible sign of Aramaic influence on Levantine Arabic.

Classical Arabic’s rich system of derived stems is also subjected to the influence of Aramaic’s symmetrical 6-stem system (three active, three passive), for instance the passive of ˀakal “he ate” isn’t ˀukil(a) as would be expected in Classical Arabic but ˀittākal (compare Syr. ˀeḵal [Pe.] > ˀeṯeḵel [Ethpe.]), likewise the passive of ˀalġā “he cancelled” isn’t the expected ˀulġiy(a) but ˀiltaġā.

Naturally, such features are not limited to Levantine Arabic alone and can be found in Mesopotamian, Egyptian and even North African Arabic. Within Levantine Arabic itself we are likelier to encounter those features in the areas where Aramaic survived the longest (in short, rural and northern Levantine dialects).

If you think the above is impressive, you might be shocked to discover just how far Aramaic’s influence goes in Hebrew.

For a start, much of Hebrew phonology, down to the tiniest details of pronunciation, is firmly rooted in Aramaic as it was spoken starting from the 3rd century BCE.

Take the plosive-spirantised realisation of the six stops mentioned above, those stops being /b/, /g/, /d/, /k/, /p/ & /t/ whereby these become /ḇ/, /ġ/, /ḏ/, /ḵ/, /f/ & /ṯ/ (AKA Begadkefat) under certain vocalic constraints such as the presence of a silent or mobile schwa. This rule is what lies behind the Ashkenazic /t/ > /s/, even though the full range of the spirants has been diminished to /b/ > /ḇ/, /k/ > /ḵ/ and /p/ > /f/ in Israeli Hebrew.

This is a hallmark of Aramaic phonology and can be found in a very similar form in Classical Syriac (there are some key differences however, the stops remain plosives after diphthongs such as /aw/ and /ay/ for instance, which is a mark of clitics in plural nouns). This spirantisation process remained productive in Assyrian Neo-Aramaic where /w/ and /u/ are now allophones of /ḇ/ (ḥaḇrā > ḫawrā > ḫōrā “friend”).

A similar development occurred in Samaritan Hebrew, we know from Samaritan grammarians that this rule affected five consonants /b/, /p/, /d/, /w/ and /t/ but not /g/ nor /k/. This still holds true to a very large extent for /p/ which has been levelled to /f/ in virtually all positions and /w/ which is realised as /b/ or /f/ in many cases, presumably from an earlier /ḇ/ (the name of the Samaritan Waw is Bå for that matter). So despite its very archaic phonology which isn’t just a facade (SH preserves geminated -imma/-inna afformative endings in 2nd & 3rd ps. pl. clitics and personal pronouns as well as the ending -tī in 2nd f. sg. perfect forms and in the 2nd f. sg. pronoun åttī, all archaic traits) its phonology was once much more aligned with Tiberian Hebrew’s standards.

Furthermore, the rules regulating the shift of Waw from /w/ to /u/ (behind /b/, /w/, /m/ & /p/) or the mutation of Schwa to Hiriq (/ə/ > /i/; think of how we say lirˀōt instead of lərˀōt, liḵtōḇ and not ləḵtōḇ, etc) is another example of inherently Aramaic vocalism setting boundaries in Hebrew, those rules tend to be identical to the ones found in Targumic Aramaic for that very reason, most of these rules also have equivalents in Samaritan Hebrew.

The ending of 3ps. masc. sg. possessive clitics on plural nouns in /aw/ (as in ˀăḇōṯāw “his forefathers”) is another feature of Aramaic phonology which spilled into Hebrew. The levelling of /ḫ/ and /ḥ/ to /ḥ/ and /ś/ > /s/ are also features of Aramaic phonology, /w/ > /v/ might also be an Aramaic sound change, though some theories ascribe this shift to contact with Greek (we do know that Waw was realised as /v/ in Tiberian Hebrew), a similar theory of Greek contact-induced change exists for the loss of gutturals in Samaritan Hebrew.

Regarding the verbal system, the active participle is the normative form of the present tense in Hebrew, once more as in Aramaic. Hebrew kōṯeḇ “writes/writing” and Aramaic kāṯeḇ are therefore squarely identical from this point of view, moreover this state of affairs clearly predates Late Biblical Hebrew.

And even though Hebrew was to a large extent successful in preserving Canaanite’s system of derived stems, the existence of Nitpaˁel is a very good example of a mixed stem (Nifˁal + Hitpaˁel) that arose under Aramaic influence in Mishnaic Hebrew and was carried over into later Hebrew (had the revitalisation of Hebrew endorsed Mishnaic Hebrew as the standard, Israeli Hebrew would be an even more Aramaic-like language).

In Samaritan Hebrew, the number of verbal stems increased from 7 to 9 (mostly via gemination of existing stems) as a reaction to the internal passive stems Hufˁal and Puˁal receding under the influence of Aramaic’s simpler 6-stem system.

Yet another area where Aramaic had a profound influence is Hebrew syntax, two examples:

The possessive pronoun šel- arose by analogy to Aramaic dil-, a contraction of dī- “of, which” and l- “to, for” (hence še [< ˀašer] + l-), compare Hbr. šelḵā to Syr. dīlāḵ; Hbr. šelāhem to Syr. dīlhon and so on.

Double possessive forms (smikhut kfula), as in ˀaḫiw šel habaḥur, are also analoguous to Aramaic constructions that can even be seen in ordinal structures such as Syr. nahrā ḏəṯlāṯā “the third river” (lit. “river of three”).

One could also point out the pervasive influence of Aramaic in Hebrew vocabulary, especially in semantic fields relating to religion and law, as a general rule the higher the register the more Aramaic lexicon we encounter. For that matter, even the words for “dad” and “mom” in Hebrew are Aramaic loanwords, namely ˀabbā & ˀimmā (to be contrasted with the formal Hebrew ˀaḇ “father” & ˀem “mother”). To say nothing of Aramaic expressions and sentences that crept into the language.

The truth is that I’m barely scratching the surface here, to make a very long story short Hebrew would be a very different language without all of its Aramaic baggage.

It must be kept in mind that the complex nature of the relationship between both languages, their common background as NWS dialects and prolonged contact over millennia often makes it exceedingly difficult to tell whether shared traits are retentions from an intermediate stage (Aramaeo-Canaanite), cases of parallel development, convergence or direct influence.

Regardless, the revivalists’ attempts to purge Aramaic influence from Hebrew was a losing battle if there ever was one (to say nothing of the square script, which displays the closest resemblance to the Imperial Aramaic script).

Three thousand years after its first appearance in Upper Mesopotamia on the lips of the marauding Aḫlamû of the Late Bronze Age, Aramaic remains the common language of the Assyrian people, a language that has since been infused with a large amount of loanwords and calques chiefly from Akkadian and Persian (as well as Arabic and Turkish to a smaller extent) and which underwent radical change as one would expect of a language spoken continuously over such a long period of time.

Aramaic is a rags to riches and back to rags story, from a set of dialects spoken by elusive semi-nomadic tribes and obscure Iron Age kingdoms vanquished by the Assyrians to being the lingua franca of its age (there was a time when speaking Aramaic meant being a man of the world) and enjoying a status similar to that of Akkadian in the Bronze Age it became a minority language confined to churches, synagogues and dwindling minorities dispersed throughout the world.

No, Aramaic is not the common ancestor of Arabic and Hebrew, that would be Proto-Central Semitic, a prehistoric language spoken more than 4500 years ago, and the Phoenicians most certainly did not speak Syriac, first because they predate the emergence of this Edessan dialect of Aramaic by many centuries and secondly because their language was a very close relative of Hebrew (or, as an astute Israeli friend of mine called it, “funny Hebrew”).

Aramaic is not “the language of Jesus” either for the simple reason that Aramaic no longer was a single language by the time he was born but rather a language family and that he spoke one of the Western dialects (Galilean Aramaic) which has been extinct for quite some time, surviving only in the form of Jewish Palestinian Aramaic (JPA) while the vast majority of present-day Neo-Aramaic languages belong to the Eastern branch (with the exception of Western Neo-Aramaic, a set of unwritten dialects, that are not descendants of Galilean Aramaic in any case).

Nevertheless, billions of people now write their language in a variant of the Aramaic script, if you can read Farsi, Malayalam, Thai, Urdu, Arabic, Sinhala or Khmer you owe your current writing system to the Arameans (courtesy of the Achaemenid empire’s linguistic policies). It is also plausible that the very concept of using signs for vowels is due by and large to the Arameans.

The major differences between spoken Arabic (Levantine, Mesopotamian and Egyptian Arabic in particular) and the Classical standard owe much to the Aramaic substrate present therein, Aramaic dialects having remained the spoken language of the Fertile Crescent well into the 10th century. The religious lexicon of Islam is also influenced by Aramaic, words such as lāhūt, malakūt or ǧabarūt are all Aramaic loanwords, Arabic’s reputed wealth in vocabulary also owes much to the accumulation of Aramaic substrata.

The rich liturgy of many Eastern Churches has its root in the Syriac tradition, and the study of Greek classics is deeply indebted to the preservation of the Classical corpus in Syriac translations (that were later translated into Arabic). While the preservation of Greek literature in the Arab empires is quite exaggerated, what was indeed preserved in the Arab cultural milieu had earlier been transmitted via Syriac.

It can even be argued that beyond being a mere product of the Nabatean script, the Syriac script was a defining influence on the morphology of the Arabic abjad’s signs (one needs not be an expert in order to notice the similarity which should be obvious just by looking at some of the manuscripts posted above).

At the beginning of this post, I said that if we were to take the Hebrew Bible’s patriarchal narratives literally, Ancient Israel must be seen as a genetically Aramean nation. While unlikely for reasons I won’t get into it is quite clear that those narratives do preserve a sense of historical truth and that the further north one went, the likelier one was to encounter people of Aramean descent, this is verified by the presence of some of the Y-lines I mentioned in Jews of all stripes alongside the minority groups mentioned in this post. Aramaic became the second national language of the Hebrew people and is firmly imbedded in its cultural, legal and religious tradition. The first translations of the Torah were made in Greek (Septuagint) and in Aramaic, Targumic literature was born out of the need to make the Hebrew Bible understandable at a time when Jewish and Samaritan audiences were far more familiar with Aramaic than with Hebrew (as a matter of fact, the current Samaritan priestly class is descended from a Levitical clan that was tasked with translating the Torah into Aramaic as it was read aloud), for this reason Targumic Aramaic straddles and blurs the lines between Eastern & Western Aramaic (the Targum Jonathan and Samaritan Targumim are inherently Western however). For many generations, Aramaic was the language of the household, it eventually became the language of prayer (still its primary function among the Samaritans, Kol Nidrei is an Aramaic prayer), marriage and mourning for Jews (hence why Ketubot and the Qaddish are in Aramaic). This long coexistence had a very profound impact on the Hebrew language of both the Jews and the Samaritans, without which it would be a different language altogether. In turn, this influence pervaded not only Hebrew but many Jewish languages of the diaspora, from Yiddish and Ladino to Yevanic and Baghdadi Jewish Arabic, all have their fair share of Aramaic loans, expressions and so forth. And of course, Hebrew (with the important exception of Samaritan Hebrew) owes its square script to Imperial Aramaic.

Last but not least, while the Arameans did not manage to maintain their identity and survive as a distinct ethnic group (present-day Maronites in northern Israel and Syriac Christians who have chosen the Aramean monicker for themselves invariably do so for reasons rooted in Church politics and not because this identity was transmitted through millennia, their liturgical use of Syriac does help legitimise the label in a roundabout way) - it is even doubtful they ever constituted a single ethnic group - their blood still runs through the veins of many today, not just the Levantine Arabs now living in their homeland (which corresponds more or less to present-day Syria along with chunks of Iraq, Turkey and Israel) but amongst many minority groups such as the Assyro-Chaldeans (with whom they blended almost completely, both willingly and forcibly), Mandæans, Maronites, Alawites, Druze and further beyond still in Italy proper and even in many parts of the former Roman empire where they were resettled.

As you can see, this post is longer than usual, I had to exercise restraint because there is a lot more to be said on the subject, it is no easy feat to summarise the history of a people and the language they have left us when there are at least three millennia of history involved. But the Arameans and their language are well worth the effort.

Every man and every race has a multitude of fathers, yet we always choose one who has the greatest personal or cultural impact.

אֲרַמִּי֙ אֹבֵ֣ד אָבִ֔י וַיֵּ֣רֶד מִצְרַ֔יְמָה וַיָּ֥גׇר שָׁ֖ם בִּמְתֵ֣י מְעָ֑ט וַֽיְהִי־שָׁ֕ם לְג֥וֹי גָּד֖וֹל עָצ֥וּם וָרָֽב