Israelites & Canaanites

In my last post, I went into some detail over how the Jews and the Samaritans are the Canaanites’ primary linguistic, cultural and biological heirs, going so far as to describe them as “watered-down Canaanites”. There is however one major aspect in which the Israelites differed significantly from the Canaanites: Their national deity.

The worship of Yahweh as Iron Age Judah and Israel’s tutelar deity does not strictly constitute a departure from the Canaanite milieu in which the Israelites emerged, in fact the model of a national (or “territorial”) kingdom with its own national deity was pretty much the norm for the Southern Levantine kingdoms of the Iron II period:

Moab had Kemosh as its national deity

Ammon had Milkom as its national deity

Edom had Qos as its national deity

A point that is too rarely taken into account is that Israel and Judah’s shared national deity decreases the odds of both kingdoms having always been separate. Yahweh worship most likely stemmed from the national cult of a unitary state that later split into both kingdoms which then inherited Yahweh worship, this would broadly mirror the events depicted in the Book of Kings, and almost certainly wasn’t the result of either kingdom imposing its state religion on the other.

Where the Israelites differ from their neighbours is the deity itself being worshipped. Yahweh is seemingly absent from all Bronze Age sources, whether hieroglyphic or cuneiform, and makes an appearance only after the Late Bronze Age collapse.

The mystery begins when we understand that Yahweh could not have been Israel’s original deity, a reality reflected in Israel’s name where the theophoric element is El, the head of the Canaanite pantheon and father of the gods (identical to Ugaritic Ilu).

Yahweh’s adoption must have intervened after the emergence of the Israelites as a distinct ethnic group in the Late Bronze Age, from the collapse of BA society to the emergence of national kingdoms, a Dark Age where there is more speculation than fact. The adoption of this hitherto unknown deity is what made the Israelites uniquely distinct from the Canaanite milieu from which they sprang forth and their no-less Canaanite neighbours. Furthermore, Yahweh’s original profile remains unclear, in order to uncover it and address this historical-religious problem we need to sift through the evidence, both internal and external to the Hebrew Bible.

(All translations below are my own)

Midianites Before Berlin

There are two competing models which attempt to explain the origins of Yahweh:

The Midianite-Kenite hypothesis

The Berlin hypothesis (thus named after its association with German scholars)

The first hypothesis enjoys more traction, mainly because of how it mirrors what the oldest layer of Hebrew poetry has to say about Yahweh’s origins and because it finds some degree of plausible support in the epigraphic record and even in the archeological record.

This hypothesis, one of the most enduring in the field of Biblical scholarship, advances the claim that since Yahweh was an outsider to the older Canaanite pantheon, his origins must be sought among the nomadic groups of Canaan’s southern desert-steppe periphery, the Sinai peninsula and northwestern Arabia, and that his worship was transmitted either via contact with those groups (such as the Midianites) or was brought by some of those nomads who settled in Canaan (the Kenites and Edomites) alongside the Israelites at the beginning of the Iron Age.

While the earliest exemplars of Hebrew poetry were possibly written down some time between the 9th and 8th centuries BCE, the archaic language of those poems (which finds many parallels in the texts of Bronze Age Emar, Ugarit and Mari) strongly suggests that they were transmitted orally over centuries, their composition likely going back to the Late Bronze Age.

The Song of Deborah is understood as embodying the most archaic layer of the Hebrew language in the entire Biblical corpus, it is also significant that it is found in the Book of Judges which is almost unanimously seen as reflecting the situation in the earliest phases of the Early Iron Age in the highlands of Judea-Samaria.

יְהוָה בְּצֵאתְךָ מִשֵּׂעִיר בְּצַעְדְּךָ מִשְּׂדֵה אֱדוֹם אֶרֶץ רָעָשָׁה גַּם-שָׁמַיִם נָטָפוּ גַּם-עָבִים נָטְפוּ מָיִם׃

הָרִים נָזְלוּ מִפְּנֵי יְהוָה זֶה סִינַי מִפְּנֵי יְהוָה אֱלֹהֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל׃Yhwh, in your going forth from Seir, in your stepping out of the field of Edom,

the earth trembled, the heavens also dripped, thick clouds also dripped water.

Mountains flowed before Yhwh [Lord] of Sinai, before Yhwh the God of Israel.

(Judges 5:4-5)

From the onset, this poem describes Yahweh marching out to battle from his abode, named in quick succession as “Seir” and “the field of Edom”, Yahweh is given the title Zěh Sinay, an archaic phrase where the first element is not the (identical) demonstrative “this” but rather serves the same function as Arabic ḏū “owner, possessor”, hence “Lord of Sinai” would be an accurate translation.

Seir and Edom which are both mentioned as Yahweh’s home are situated in Canaan’s southern desert periphery, Seir also appears alongside Sinai in another archaic poem, the Blessing of Moses (Deuteronomy 33:2).

Outside the Hebrew Bible, Sˁrr “Seir” makes an appearance in the New Kingdom topographic lists of the temples of Soleb and Amara West in Nubia (respectively dating back to the 14th and 13th centuries BCE), detailing several tribes of the Shasu, nomadic pastoralists who encroached on Egyptian trade routes. More importantly, among those Shasu nomads is another group known as the “Shasu of Yhwꜣ” in what might be the first mention of the deity by name, going back to the Late Bronze Age.

This somewhat enigmatic mention has confused many, as the list ties the Shasu clans to specific areas from which they hail, Yhwꜣ is thus best understood as a place name (or even a tribal name). Still, the close geographic association between Yahweh and those southern areas isn’t entirely problematic, the region from which this group hailed might have easily been named after the deity altogether.

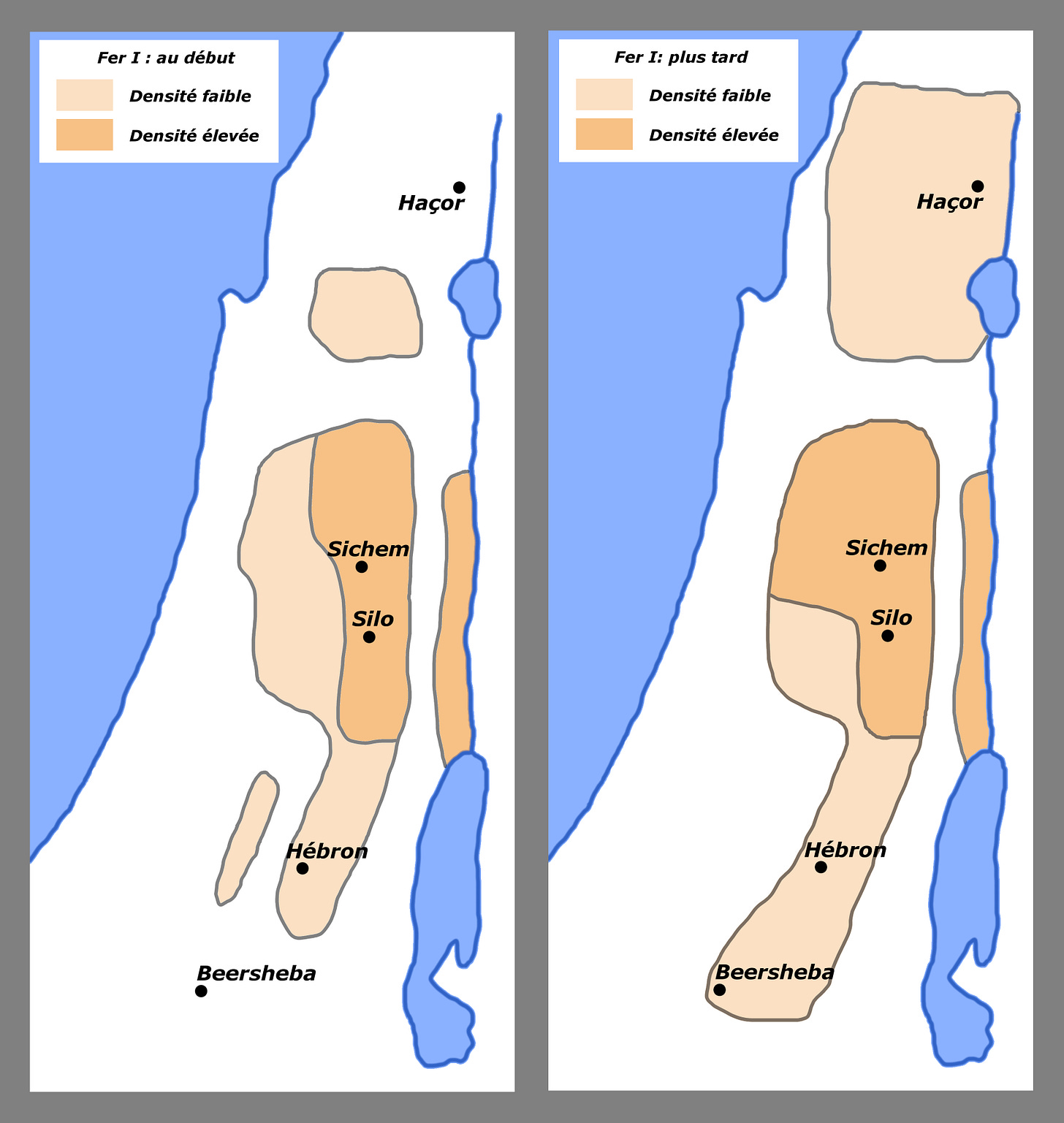

Several scholars (Donald Redford and Anson Rainey to name but a few) have considered this datum sufficiently compelling to posit an identification between the Shasu and the Proto-Israelites. From a narrower archeological standpoint, this could work if we endorse the view (espoused by Israel Finkelstein and Avraham Faust) that the Iron I settlement in the Judean & Samarian highlands was a phenomenon rooted in Transjordanian nomadic clans arriving in a set of migrations from the east, that being said the evidence linking those pastoralists to the inhabitants of the Negev and northwest Arabia is flimsy.

Midian-Edom-Cain Nexus

The notion that Yahweh was transmitted to the early Israelites through contact with the Midianites is found in the Wilderness narrative and its description of Midian, whence Moses first encounters Yahweh and whose father-in-law is described as “the priest of Midian”:

וּמֹשֶׁה הָיָה רֹעֶה אֶת-צֹאן יִתְרוֹ חֹתְנוֹ כֹּהֵן מִדְיָן וַיִּנְהַג אֶת-הַצֹּאן אַחַר הַמִּדְבָּר וַיָּבֹא אֶל-הַר הָאֱלֹהִים חֹרֵבָה׃

Moses was shepherding the flock of Jethro, his father-in-law, the Priest of Midian, and led his flock into the desert and came to the Mountain of the Elohim, to Ḥoreḇ.

(Exodus 3:1)

Here too, we see that Yahweh is tied to a “Mountain of the Elohim”, which echoes the toponymic nature of the Shasu lists. The portrayal of the Midianites in the Hebrew Bible is quite ambiguous however, if they are depicted in the Wilderness narrative as a friendly group with which Moses freely intermarries and with whom the Israelites seem to share their faith in Yahweh, they are more often described as enemies of Israel.

It is the Midianites (often confused with the Ishmaelites) who sell Joseph as a slave in Egypt. Moses himself wages war against the Midianites and kills five of their kings, all vassals of the Amorite Siḥōn (Numbers 31). In Judges 6 (right after the Song of Deborah), the Midianites are raiding and enslaving the Israelites as punishment for their impiety, they are delivered by Gideon who captures and executes the Midianite chieftains ˁŌrēḇ “Crow” and Zəˀēḇ “Wolf” before taking the fight into Midianite territory and doing the same to two of their kings, one of whom bears a very peculiar name:

וַיָּקָם גִּדְעוֹן וַיַּהֲרֹג אֶת-זֶבַח וְאֶת-צַלְמֻנָּע וַיִּקַּח אֶת-הַשַּׂהֲרֹנִים אֲשֶׁר בְּצַוְּארֵי גְמַלֵּיהֶם׃

Gideon rose up, killed Zəḇaḥ and Ṣalmunnāˁ and took the crescents on their camels’ necks. (Judges 8:21)

Ṣalmunnāˁ is — much like Israel — a theophoric name, containing the name of a deity known as Ṣalm which appears in several Taymanitic texts. Taymanitic was a language spoken during the first half of the 1st millennium BCE in northwestern Arabia close to the oasis of Taymā, this language seems to have been of the Northwest Semitic type (meaning it shares a more recent common ancestor with Canaanite, Aramaic and Ugaritic than it does with Arabic).

Midian shows up in a Taymanitic text discovered in 2012 in Wādī al-Zaydāniyyah, south of Taymā in Tabuk Province, possibly dating back to the Iron IIA considering the morphology of the letters. This is important as it provides external attestation of Midian, which can no longer be dismissed as a mere product of Judahite scribal imagination. The context is also crucial, regardless of the boast inherent to the inscription, there is good reason to suspect that the Midianites were either akin to the Taymanites or spoke a form of Taymanitic.

While Yitrō “Jethro” features a final /w/ typical of Old Arabic names (think of Gashmu the Arab or Gindibu the Arabian from the Kurkh monoliths), his name undoubtedly is the Midianite version of Wtr, a personal name found in other Ancient North Arabian inscriptions. The catch however is that this name partakes in the word-initial /w/ > /y/ shift which is a hallmark of NW Semitic and is present in Taymanitic inscriptions.

The identification between the Midianites and the Taymanites also finds some degree of support in the archeological record, the painted pottery of Tayma appears to be a local variant of Qurayyah Painted Ware (QPW) which is usually understood to be tied to the Midianites, there is also some overlap between those and Edomite pottery (STNP) which appears in the Negev during the Early Iron Age.

Leaving those subtleties aside, if we assume the Midianites worshipped Ṣalm as their chief deity, we might need to look elsewhere for Yahweh’s origins.

What of Edom and the Kenites? The former are said to have battled against the Midianites in Genesis 36, and as we’ve seen above Yahweh is described as stepping out of the “field of Edom”.

The earliest mention of Edom is to be found in Papyrus Anastasi VI (13th century BCE), the Hebrew Bible traces the Edomites back to Esau, Israel’s brother, thereby making them close relatives of the Israelites. From the few Edomite inscriptions discovered so far (mostly ostraca), they were linguistically Canaanite.

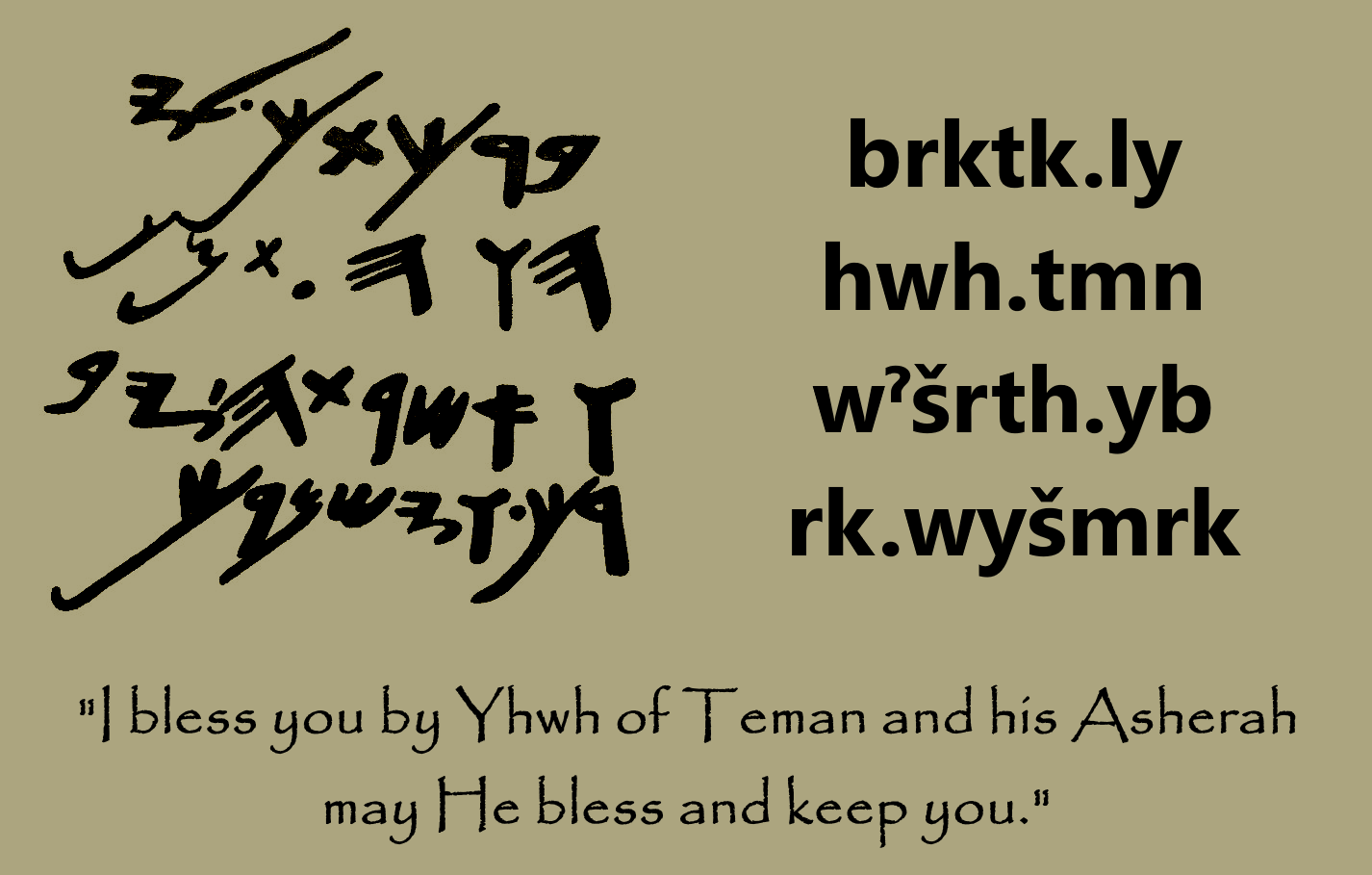

At Ḥorvat Teman (Kuntillet ˁAjrud), a caravanserai (likely established by the kingdom of Judah) which also served as an early pilgrimage site, several late 9th century inscriptions refer to Yahweh alongside other deities such as El, Ba’al and Asherah, some closely mirror the poetic language of the passages discussed above. One inscription in particular contains a blessing where “Yahweh of Teman and his Asherah” are invoked.

The mention of “Teman”, a word usually meaning “south” in Classical Hebrew, brings us back to Edom. In Genesis 36, “Teman” is listed as a bona fide Edomite clan:

אֵלֶּה אַלּוּפֵי בְנֵי-עֵשָׂו בְּנֵי אֱלִיפַז בְּכוֹר עֵשָׂו אַלּוּף תֵּימָן אַלּוּף אוֹמָר אַלּוּף צְפוֹ אַלּוּף קְנַז׃

These are the chiefs of Esau’s sons:

Sons of ˀĚlip̄az the firstborn of Esau:

chief Tēman, chief ˀŌmār, chief Ṣəp̄ō, chief Ḳənaz.

(Genesis 36:15)

Pay attention to the last name, Kenaz, we’ll be coming back to it shortly.

Another basis for comparison would be the Blessing of Moses which potentially mentions Asherah in an oblique manner:

וַיֹּאמַר יְהוָה מִסִּינַי בָּא וְזָרַח מִשֵּׂעִיר לָמוֹ הוֹפִיעַ מֵהַר פָּארָן וְאָתָה מֵרִבְבֹת קֹדֶשׁ מִימִינוֹ אשדת לָמוֹ׃

And he (Moses) said: Yhwh came from Sinai, he dawned from Seir for them, he shone from Mount Paran and came from the myriads of Ḳōděš, at his right [was] ˀšdt for them.

(Deuteronomy 33:2)

The word ˀšdt in this enigmatic passage is gibberish, and very likely a scribal error where the original version had Resh instead of Dalet, two very similar letters in the Paleo-Hebrew script (and still today in the Square Hebrew script), leading us to the reading ˀšrt “Asherah”.

The mention of Kenaz brings us to the Kenites. Unlike Midian and Edom, the Kenites are unattested outside the Hebrew Bible, we are then entirely dependent on Biblical sources. The Kenites’ name is etymologically-related to metal-working based on Aramaic and Arabic comparanda, they are indeed described as itinerant smelters and are thought to be Cain’s descendants (of Cain & Abel fame). At the beginning of the Book of Judges, Moses’ father-in-law is labeled a Kenite, not a Midianite:

וּבְנֵי קֵינִי חֹתֵן מֹשֶׁה עָלוּ מֵעִיר הַתְּמָרִים אֶת-בְּנֵי יְהוּדָה מִדְבַּר יְהוּדָה אֲשֶׁר בְּנֶגֶב עֲרָד וַיֵּלֶךְ וַיֵּשֶׁב אֶת-הָעָם׃

And the sons of the Kenite, the father-in-law of Moses, went up from the City of Palm Trees with the sons of Judah [to] the Desert of Judah which is in the south of Arad,

they went and dwelled with the people.

(Judges 1:16)

In the Song of Deborah, the Kenites are described as fighting alongside Israel against Sisera and Jabin of Hazor, to make a long story short they are often tied to the Kenizzites who feature prominently in the conquest narratives surrounding Caleb, son of Yephunneh, himself a Kenizzite. Nevertheless, Kenaz is listed as an Edomite clan alongside Teman as we’ve seen above, which adds another layer of complexity.

The Kenizzites clans are said to have settled in and around Hebron, which would become king David’s first capital.

Closer ties between Yahweh and Edom would explain the absence of polemic against Qos, Edom’s national deity, in the Biblical text and might even hint at a common background for both deities, but this is really an argument from silence (for that matter one could make the same argument with Ṣalm). The Kenites have an objectively better shot at being the group that brought the cult of Yahweh to Israel, that is unless we prioritise the Kenizzites’ Edomite genealogy (which would make them practitioners of the cult of Qos instead).

Looking at the tribes of Israel, three stand out as potential sources for early Yahweh worship, those being Levi, Simon and Judah. The first two tribes notoriously lack any tribal allotment (pointing to an exogenous origin) and are often lumped together (as in the Rape of Dinah and the Blessing of Jacob), the Levites are very strongly associated with the Exodus and Wilderness narratives and at least one of their clans is listed in Genesis 36 among the Edomite clans, one of their families is also named after Hebron, likewise Judah seems to have been a constellation of nomadic clans (including the Calebites-Kenizzites).

In summary, the process of transmission of Yahweh from the south is unlikely to have been restricted to a handful of Shasu tribes making their way to EIA Israel, there’s a slew of contenders at our disposal which means it must’ve been a rather continuous affair largely tracking repeated waves of semi-nomadic clans, originating in northwestern Arabia and the Arabah, settling in the Negev starting from the 12th century BCE and continuing well into the 6th century BCE.

The intensification of those waves of nomadic settlers could explain the discrepancies between Judahite and Israelite forms of Yahwism, with Judahite religious practice staying closer to the originally aniconic and austere nature of the cult of Yahweh because of greater exposure and integration of families of Midianite or Negevite descent in Judah, while Israelite religious practice in the north displayed more syncretism as it enshrined the centrality of pilgrimage and communal feasting that seems to have been a salient feature of Yahweh’s cult, explaining the nature of Elijah’s pilgrimage from Israel to Ḥoreḇ.

וַיָּקָם וַיֹּאכַל וַיִּשְׁתֶּה וַיֵּלֶךְ בְּכֹחַ הָאֲכִילָה הַהִיא אַרְבָּעִים יוֹם וְאַרְבָּעִים לַיְלָה עַד הַר הָאֱלֹהִים חֹרֵב׃

וַיָּבֹא-שָׁם אֶל-הַמְּעָרָה וַיָּלֶן שָׁם׃He arose, ate, drank and went sustained by that meal

for forty days and forty nights until the Mountain of the Elohim, Ḥoreḇ.

He came there to the cave and spent the night therein.

(1 Kings 19:8-9)

Even though some scholars (such as Amzallag) emphasise the metallurgical and volcanic qualities of this deity (which aligns with the Kenites’ status as metalworkers), the original profile of Yahweh is more convincingly that of a war god or a divine warrior granting victory on the battlefield to his followers.

Yahweh’s ultimate origins would be among a set of early North Arabian deities alongside Qos (whose name, etymologically related to the Arabic qaws “bow”, also points towards a war god) and Ṣalm (possibly meaning “image”, hinting at aniconism), all of which might be manifestations of the pan-Semitic god ˁAṯtar, this would also explain the more localised and tribal aspect inherent to these deities.

Finally, if we accept Yahweh’s origin among proto-historical North Arabian tribes, from a genomic perspective we should expect this transmission to be reflected by a steady influx of Ancient North Arabian admixture trickling into IA Israel.

Tentatively, several Y-Chromosomal lineages found among Jews that have unambiguous LBA and EIA Arabian ties are potential candidates for such an association, some of the best examples would include J-ZS2121 (downstream from FGC8712, under which we find the Qurashite J-L859) and E-BY11629, but this is mere speculation at this stage even if those lineages fit the bill.

In the next part, we’ll be looking at the shortcomings of the Midianite-Kenite hypothesis and focus more closely on the Berlin hypothesis.

This is fascinating. It raises the question of Ur/modern day Iraq, from which Abraham and Sarah are said to have come. Of course he could have come to the land and if his offspring married with those Canaanite or Arabian tribes you mentioned, then it all follows.

Very important clarification of the God of Israel's connection to the southeastern regions of Seir/Edom, Paran, Midyan, Horeb, Sinai, etc. I would only add that the need to distribute the various facets of this process to a hypothetical multitude of "waves" may be a function of our limited understanding of each individual proposed "wave." We may eventually realize that only one "wave" was primarily responsible and that we were unable to come to this conclusion earlier due to the limited nature of our evidence. For me personally, occam's razor points in that direction. If this process is in fact the result of multiple ways it would be an interesting and for me a new way to conceptualize historical events.