The predominance of a given Y-DNA lineage in a neatly defined segment of a wider language family is nothing new, to use a few familiar examples we see this with I-M253’s branches among Germanic-speaking groups, their association with the Germanic languages is bound to go all the way back to the Nordic Bronze Age and the Battle Axe Culture (I-M253 hence took part not only in Germanic dispersals but was present in the intermediate stages that separate the Germanic Parent Language from its Late IE ancestor), we also see this with branches of J2a such as M319 and the Hellenic languages.

In all of those cases we are dealing with lineages that have no external correspondence to the wider Indo-European family (for which R-M269 and R-M417’s branches are the main correlates) and were incorporated in-situ once early IE tribes made their way to Eneolithic Scandinavia and the BA Aegean. This is also fairly straightforward considering the presence of an easily identifiable pre-IE substrate in both branches of the IE family (which are sometimes described as being the “least Indo-European” despite this being very misleading language).

I do not wish to engage in monomaniacal discourse surrounding J-P58, its origins, spread and the like, it is not “the” Semitic marker in any case but rather one out of many, however the J lineages that are so common in Semitic-speaking groups both modern and ancient seem to be a similar case and deserve a serious explanation.

Those lineages essentially comprise branches of J-P58, J-Z1853 is the main correlate as well as the most successful branch of the lot and its phylogeny mirrors the Semitic language tree closely enough in both time and space for it to be a Proto-Semitic marker though it must be stated that it is not the only P58 branch that is a Semitic marker, many others such as BY111, L860, ZS5383 and P56 (which is not P58) are every bit as likely to have been carried by the earliest Semitic speakers. In fact all of P58 except for one or two smaller branches can be seriously viewed as a Semitic marker.

To this we must add branches of J-M205 which is very common among the inhabitants of Soqotra and consistently shows up in ancient remains tied to Semitic-speaking cultures all the way back to the Early Bronze Age, often alongside J-Z1853…

And yet, there seems to be no straightforward explanation for the presence of those J lineages which otherwise have no clear ties to the other branches of the Afroasiatic macrofamily of which Semitic is but one branch (and for which E-M35’s branches - especially those under E-M34 as far as Semitic is of concern - are the best correlates).

Surely, if these lineages ultimately originated in a non-Afroasiatic setting, their forebears must have left traces of their old tongue in Semitic?

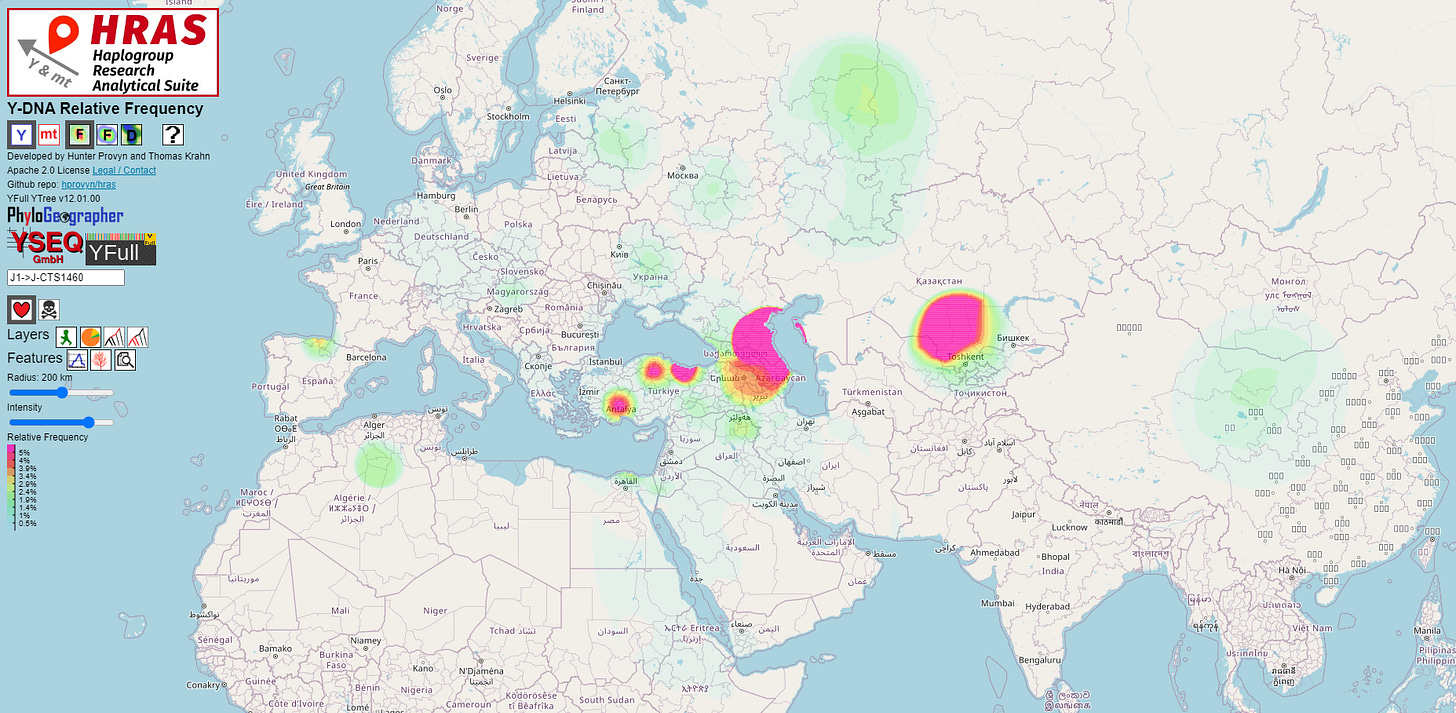

After adding the ancient Georgian samples from Skourtanioti et al. to the ancient J-P58 map, the deep-rootedness of those lineages in the Southern Caucasus and its immediate surroundings is becoming hard to ignore.

The sheer ubiquity of J-Z1828 and especially its CTS1460 subclade in EBA (Kura-Araxes) and later Hurrian and Urartian samples as well as at least one Caucasian Albanian sample makes it quite clear that the relationship between Hurro-Urartian and Northeast Caucasian (to which Chechen, Ingush, Lezgin, Avar and about thirty more obscure languages belong) is a genetic one and that there’s no escaping the fact that the Alarodian phylum put forth by Starostin is looking increasingly real, it is almost impossible to explain what we’re seeing without some sort of genetic relationship being involved.

Alarodian might well be one of the first cases where a somewhat controversial (not to say daring) linguistic hypothesis finds itself tremendously strengthened by the ancient genomic evidence. Indeed while the linguistic argument behind Alarodian always was a bit wobbly, thanks to the often less than compelling methods espoused by the Moscow school, the theory of a genetic relationship between Northeast Caucasian and Hurro-Urartian was never unconvincing.

Again, this is despite our inability to confirm Alarodian’s existence with the normal tools of linguistic comparison at our disposal. This might not sound like a big deal, but it must be stressed that it absolutely is, we might effectively be witnessing how ancient genomic data has the power to redefine not just issues of internal classification but to provide important clues and avenues for future research in the classification of languages that are usually thought of as isolates.

Coming back to the J lineages, despite the branches now firmly entrenched among Semitic-speaking groups (chiefly under P58 and P56) and those found in ancient Hurro-Urartian samples and present-day NEC-speaking groups having their most recent common ancestor some 17,000 years ago, they stand out even more now considering the lack of any plausible external relation that would anchor those lineages in an Afroasiatic setting while we have cause to suspect some kind of relationship to the ancestor of both Northeast Caucasian and Hurro-Urartian.

The families included within the Alarodian family, namely Northeast Caucasian and Hurro-Urartian, share a very specific typological feature that was once widespread in ancient Near Eastern languages such as Hattic and Sumerian.

These languages all have ergative-absolutive alignment whereby the subject or agent of a transitive verb is marked with a special case (ergative) while the subject of an intransitive verb and the object of a transitive verb take the same case (absolutive, usually unmarked in those languages).

This might be surprising to some but it has long been known that an ergative substructure can be discerned in the polysemic nature of Akkadian, Eblaite, Geˁez, Hebrew, Mehri and even Aramaic statives, especially in the suffix conjugation (see C.H.P. Müller, “Ergative Constructions in Early Semitic Languages”; 1995).

This has sometimes been compared to Egyptian statives (notably by Loprieno). Likewise Sasse (1984) reconstructed an absolutive case *a for Proto-(East) Cushitic and Proto-Berber, which fits nicely with Semitic’s position within Afroasiatic as those two are its closest relatives, because of this Macro-Cushitic (the ancestor of Semito-Berber and Cushitic) could have had a marked nominative system, on the other hand a hypothetical ergative case for a Pre-Proto-Afroasiatic stage is hardly retrievable.

The absolutive case is also retained in diptotic plurals as the accusative or oblique case. If the accusative -a preserves an older absolutive function, the nominative -u should embody the ergative. This correspondence between the accusative -a and an absolutive function is most clearly visible in Amorite personal names where the theophoric element ends in -a as well as in Amorite loanwords in both Akkadian and Egyptian sources. This is in-keeping with the archaic properties preserved in personal names. In other words, the early Semitic accusative takes up several functions of the absolutive case which marks the subject of an intransitive verb or the object of a transitive verb.

Because the East Semitic and Northwest Semitic branches underwent sustained contact with languages of the ergative-absolutive type such as Sumerian and Hurrian, it is preferable to focus on branches that were not in immediate contact with such languages in order to verify the validity of those features.

Traces of the absolutive survive in Arabic’s verbal sentences comprising kāna “to be” and its “sisters” (laysa, ṣāra, ˀaṣbaḥa, bāta, ẓalla, mā zāla, etc) whereby the predicate is in the accusative case -an, as in al ˀamr-u muˁaqqad-un > kāna (a)l ˀamr-u muˁaqqad-an.

In Geˁez ሃ -hā is the accusative marker used for personal names (e.g. Dawit walada Salomon-hā) while the accusative case is normally -a, the latter is also applied to the predicate of the verb kona “to be” (e.g. kona kahēn-a) which mirrors what we see in Arabic with kāna and its “sisters”. There are similar traces of the absolutive case in Mehri as well as other MSA languages.

The appearance of those features in Arabic, Ethiopic and Modern South Arabian enables us to push their existence all the way back to their common West Semitic ancestor, furthermore their sheer isolation from languages of the ergative-absolutive type means that the identity between the absolutive quality of the accusative in these languages and in Akkadian (and Amorite) further confirms the presence of this absolutive case in Proto-Semitic.

Some (Satzinger) have explained these features as leftovers of an older marked nominative system (AKA nominative-absolutive), especially considering that this kind of typological alignment is cross-linguistically rare, by and large restricted to the Afroasiatic and Nilo-Saharan families. One must keep this possibility in mind, Semitic’s nominative-accusative system could have arisen out of a marked nominative one in Semito-Berber and Macro-Cushitic before that.

While the retention of the absolutive case all the way back from Afroasiatic is possible, a more plausible explanation in my view is that the shift from a marked nominative system to the nominative-accusative one was a fuzzy process and that this was driven by language contact, in which case we are not dealing with an internal development but rather with the leftovers of a language related to or even derived from the Caucasic or Alarodian stock.

As a rule of thumb, and this counts for most reconstructed languages out there (Proto-Indo-European included), what was lost is generally greater than what has come down to us. The language we call Common Semitic or Proto-Semitic was not uniform and the appearance of its reconstruction owes a lot to the dialect clusters that thrived most, the language itself must have been riddled with contradictory elements, and that would have included different degrees of typological alignment from an older (presumably AA) marked nominative one to one which was more pristinely of the nominative-accusative type but preserved aspects of an ergative system the further back we go in time.

If we look closely enough, one can indeed discern traces of a non-AA Near Eastern substrate language of the ergative-absolutive type scattered throughout the earliest layers of Semitic speech, I could go into more detail and highlight how this is a more convincing option based on the form of the ergative case but the linguistics would invariably bore an unaccustomed audience. Needless to say, this provides a much better fit for the predominance of the J lineages among early Semitic speakers than an explanation appealing to internal derivation for those bizarre features, one which has the advantage of making the linguistic and the genetic evidence correspond and would therefore explain their intrusive nature.

This shows that while the J lineages were almost certainly not part of the Afroasiatic milieu from which Semitic branched off, the antiquity of those features having already been present in at least some of Common Semitic’s early dialects - and reconstructible in part because the success of this language family was largely accompanied by the spread of J lineages, older variants of Proto-Semitic might’ve lacked them altogether - suggests they were not “Semitised” either but already well-entrenched among the Proto-Semites and therefore that the accretion of those lineages was already well underway when the Semitic Parent Language was still spoken.

Finally the conspicuous situation of Semitic, a language family about as old as Indo-European, which came to be associated chiefly with a paternal lineage that does not reflect Common Semitic’s Afroasiatic past beyond the immediate Pre-Proto-Semitic stage should serve as a cautionary tale.

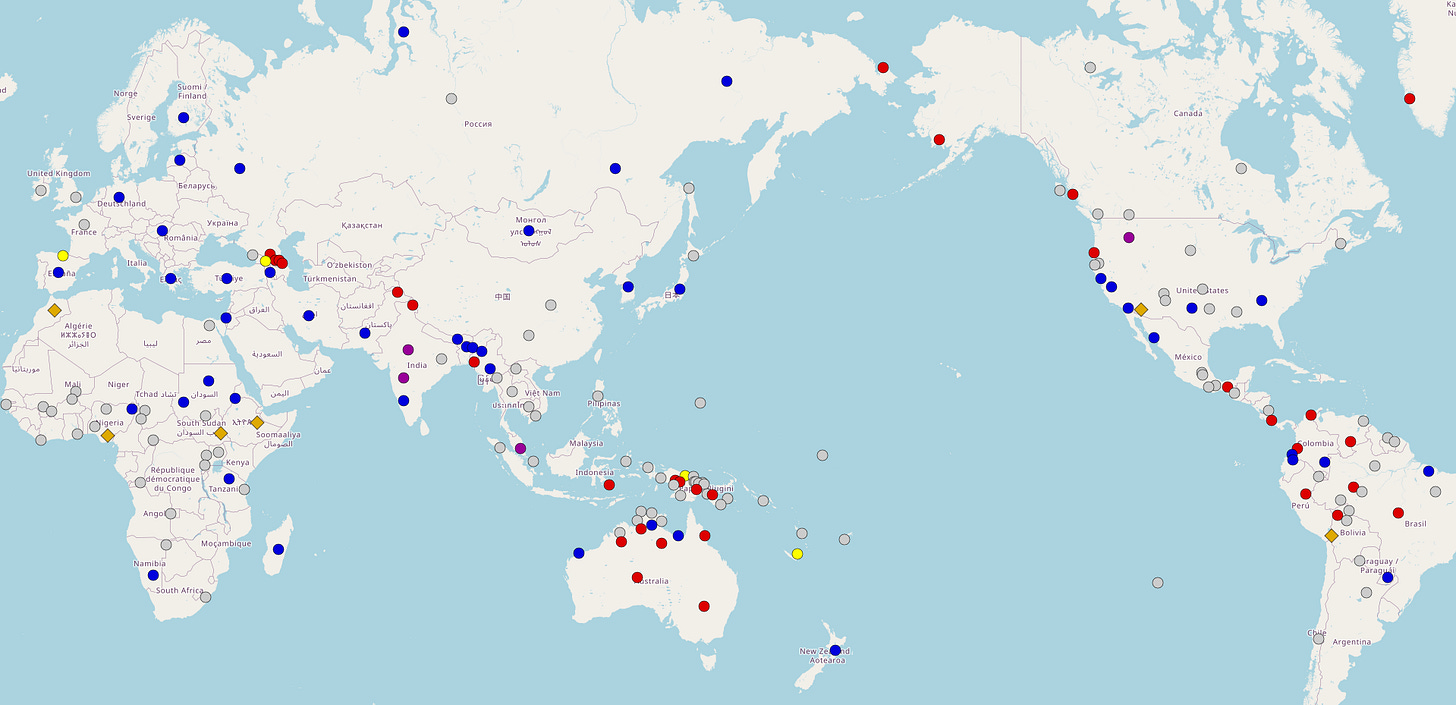

So here’s some food for though: While I am supportive of the notion that R-M269 and R-M417 alongside EHG (as the accompanying strand of ancestry) are the best candidates for Proto-Indo-European’s deep linguistic past, we must keep an open mind considering the presence of other lineages in early IE remains such as R-V1636, Q-L933 and especially I-L699 in Sredny Stog as well as J-L283 in a Yamnaya sample from Moldova (this should put to rest the debate over L283’s involvement in early IE dispersals, we’re clearly dealing with an IE marker, just like J-M205 is a Semitic one), the fact of the matter is that this kind of patrilineal heterogeneity leaves the door open to a variety of scenarios in the absence of any clear-cut information on IE’s external or high-level relationships, this of course applies not only to PIE but to every major phylum which displays that kind of heterogeneity.

Excellent

Gishmak story, loved to read, but one correction, we all know I-Y16419 was the Y of the original Semites ;)